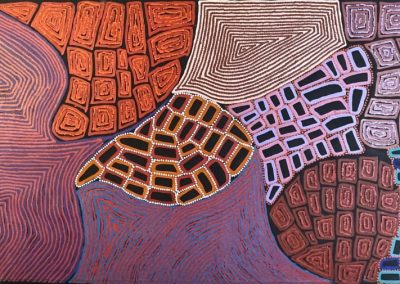

Warlimpirrigna Tjapaltjarri, Thomas Tjapaltjarri and Walala Tjapaltjarri Collaboration Tingari Painting

Collaboration Tingari Painting by Warlimpirrnga, Thomas & Walala Tjapaltjarri

Size: 203cm x 104cm

Medium: Acrylic on Canvas

Price: POA (Price on Application)

A Masterpiece of the Tingari Cycle

This extraordinary Collaboration Tingari Painting brings together the artistic vision of three renowned Pintupi artists: Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Thomas Tjapaltjarri, and Walala Tjapaltjarri. Their work captures the deep spiritual and cultural significance of the Tingari Cycle, a sacred and mythological series of Dreaming stories passed down for generations.

The Tingari Dreaming is deeply tied to the artists’ birthplace in the vast sandhill country of the Western Australian desert, depicting ceremonial sites, sacred mountains, rockholes, and water sources. Using bold geometric designs and intricate dot work, this painting is a powerful representation of an unbroken cultural tradition stretching back tens of thousands of years.

The Artists & Their Legacy

The Tjapaltjarri brothers—Warlimpirrnga, Thomas, and Walala—were part of the Pintupi Nine, a group of Indigenous Australians who lived a completely traditional, nomadic lifestyle in the remote Gibson Desert until they made contact with modern society in 1984. Their arrival made international headlines, earning them the title of “The Last Nomads” or “The Lost Tribe.”

-

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri is an internationally acclaimed Indigenous artist known for his hypnotic, optical paintings that depict the desert landscape and Dreaming stories. His works are showcased in prestigious institutions worldwide.

-

Thomas Tjapaltjarri began painting in the early 2000s, inspired by his brothers. His work features a bold, gestural style, often using rectangular shapes and intricate dot work to depict the sacred sites of the Tingari Dreaming.

-

Walala Tjapaltjarri developed his own unique style, abstracting classical Pintupi designs to create striking geometric compositions that map his ancestral country and ceremonial sites.

A Rare & Collectible Work of Art

This collaborative piece is a rare and highly sought-after artwork, bringing together the distinct styles of three celebrated artists. With Warlimpirrnga and Walala achieving international acclaim, and Thomas’ powerful compositions gaining strong recognition, this painting stands as a testament to the endurance of Pintupi culture and the deep spiritual connection between art and Country.

📩 Enquire today to own a piece of Aboriginal art history.